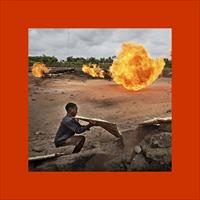

NIGERIA: Rising risk in the delta

The deployment of additional troops to Nigeria's restive, oil-soaked delta has managed to improve security, but not even their commanders believe there can be a military solution to the armed young men in the creeks, willing to back their demands for a greater share of the wealth their region produces by attacking oil facilities and the soldiers guarding them.

Fighters of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), one of several militant groups operating in the southern region, blew up two major oil pipelines owned by Shell at the end of July, but the Nigerian military has pledged to use minimum force in restoring order, to create conditions conducive to a political settlement.

Critics say the problem is that despite the government's public commitment to resolving the crisis, there has been little progress in tackling the deep-seated poverty and neglect, unanimously regarded as the only way forward.

The alternative is the chaos of August 2007 in Port Harcourt, capital of Rivers State and the headquarters of the oil and gas industry in the delta. Politicians had armed out-of-work young men, who used the guns in kidnappings and turf wars, killing over 100 people in Port Harcourt before the deployment of a security forces Joint Task Force (JTF) managed to put a lid on the chaos.

"One can say there is peace in Port Harcourt, but are the conditions that gave rise to the gangsterism and killings resolved? The answer is 'No'," commented journalist Akanimo Sampson. "What you have seen [the insurgency] is a political device by the youths to draw the attention of the authorities to the unsettled issues in the oil and gas-producing regions of Nigeria."

Many in the core four southern states of the delta say the time for talking is over. They want a settlement based on the 2005 findings of a committee chaired by Lt-Gen Alexander Ogomudia, which called for the federal government to spend 50 percent of the revenue derived from the delta in the region, and for laws dispossessing people of their land to be repealed.

They also demand the freeing of militant leader Henry Orkah, transparency in federal government funding of the Niger Delta Development Commission, job opportunities, and implementation of President Umaru Yar'Adua's election promise of a Marshall Plan for the area.

But civil society activist Isaac Osuaka sees the crisis at a much more fundamental level. He argues that until a deeply corrupt political system, which denies real democracy and licenses wholesale looting of resources, can be reformed, the instability will continue.

"If communities could directly elect their political representatives [without rigging] you would automatically disarm the militants," he told IRIN/PlusNews. Until then, "We will have moments of quiet and moments of disturbance."

Dr C. Okeh, who chairs the State Action Committee on HIV/AIDS (SACA), worries that the unrest will undo the work his committee and non-governmental partners are doing in the region. At the very least, "A crisis situation means that you don't have time to listen to [AIDS] messages - you're thinking of your immediate survival," he told IRIN/PlusNews.

HIV risk

"Rape is prevalent; these militants do anything they like, and when there is conflict the military move in, and they too will commit rape," said Okeh. SACA works with the police and the army's 2 Brigade, headquartered in Port Harcourt, both of which have well-established AIDS programmes, but the JTF, a federal taskforce, falls outside SACA's umbrella.

Rivers State has an HIV prevalence of 5.4 percent - one point higher than the national average of 4.4 percent - and has risk factors that could drive those numbers higher.

Port Harcourt has a sea port and an international airport, and is a magnet for migration. According to a National HIV/AIDS and Reproductive Health Survey, the region has the highest incidence of sex in exchange for gifts or favours, the largest numbers of people who have sex with more than one partner in a year - and they drink more alcohol than anyone else.

"Rivers State is dotted with oil and gas activities, and commercial sex workers follow the camps," said Okeh. "We are finding a rising [HIV] prevalence in rural farming and fishing communities - we have communities with very high unemployment rates."

Rivers State has an estimated 120,000 people living with HIV and roughly 5,230 currently on antiretroviral treatment (ART), accessed through seven public health centres.

One of those, on Bonny Island, a one-hour boat ride from Port Harcourt, has been irregularly supplied due to the threat of piracy. "Because of the insecurity we can't move in drugs and other supplies to the site - nobody is prepared to risk his/her life," said Dr David Fabara, coordinator of ART/surveillance in the state. "We suspect there definitely will be a problem of [drug] resistance [as a result of treatment interruption]."

Eleme, on the edge of the creeks, one hour's drive from Port Harcourt, is another area with a history of unrest. Its oil refinery is the country's oldest and has been at the centre of communal tension between the Okrika people and the Eleme over ownership of the land on which the facility sits - and therefore potential royalties.

A sprawling commercial sex industry has sprung up outside the refinery gates to cater to the needs of long-distance tanker drivers, traders and oil workers. But soldiers based at the nearby river jetty, who have come under intermittent attack from the young militants, have imposed a 9 p.m. curfew on the sex trade to keep people off the streets.

It is enforced by regular raids on the shacks, kicking out customers, switching off lights and roughly forcing women into their rooms, according to sex workers IRIN/PlusNews spoke to. Charity Ekititi said she was raped three weeks ago by a soldier. "They f*** you through their uniform [by virtue of being soldiers]. He used a condom [but didn't] give me money."

Her friend Patience Okada* was equally furious at the treatment. "Army people are disturbing us, they chase customers, flog us ... People tear race [run], one leg of slippers still dey for my room [in his haste a customer left a sandal behind]." With the lights off, armed robbers were becoming another problem. "They come [and] knock, you open your door, they steal your cell phone, your money."

Queen Henry, a peer educator for the sex workers in the area, who has been developing a small side business selling tonics and douches, said she was being forced to go back on the game. "If I don't hustle again my [income will be] down," she explained. Some of the women in her group, fed up with the harassment, have moved to other commercial sex sites in the state.

The insecurity is "very challenging, because we are in a situation of a widespread epidemic with very high prevalence across the state, even in the interior", said Okeh.

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also