GLOBAL: Defining the Rights of the Internally Displaced

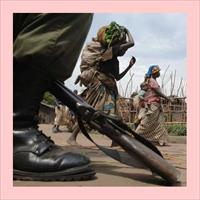

At least 26 million people across the world are displaced within their own countries because of armed conflict. Another 50 million have been made homeless by natural disasters and experts predict that the effects of climate change, population growth and poverty could increase that number to 200 million by 2050.

The plight of internally displaced persons (IDPs) often takes centre stage in humanitarian operations and the first universal guidelines detailing the rights of uprooted populations, known as the Guiding Principles for Internal Displacement, were drawn up in 1998.

This week, a high level conference in Oslo, Norway on 16 and 17 October will assess their first 10 years and evaluate the future.

In contrast to international humanitarian legislation, the 30 articles that constitute the Guiding Principles are ‘soft law’, meaning they have no legal standing of their own. Instead they refer to a broad range of already existing international human rights and humanitarian laws.

Rights and obligations

A key point of the Principles is that IDPs have equal rights and obligations. The fact that a person has been made homeless should not necessarily reduce his or her rights as a citizen. The Principles also hold that national governments are directly responsible for protecting their own populations, and that when they cannot do this, or choose not to, the international community has an obligation to guarantee the IDPs’ protection.

Walter Kälin, the UN Secretary General’s Special Representative for the Human Rights of IDPs, said that before the Guiding Principles, the displaced were frequently overlooked in humanitarian operations. “They were totally neglected,” Kälin said. “They were not refugees [they had not crossed a national border], and often they were not included in humanitarian programmes.”

Kälin said it was eventually realised that IDPs had special needs requiring specific attention. “If you are not displaced, you don’t need to find shelter,” he said. “You don’t have to worry about not speaking the language or how you are going to earn your next day’s living, or getting your property back.”

The Guiding Principles have set a common set of standards that national governments, UN agencies and international relief organisations can refer to in displacement situations.

“Ten years ago they weren’t seen as something that you would use every day,” said Lea Matheson, IDP advisor for the International Organization for Migration (IOM). “Now my operational colleagues use them to guide projects they are developing. For me, they have gone from a legal framework to a very tangible operational document.”

Influencing national legislation

Kate Halff, who heads the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), a project backed by the Norwegian Refugee Council, said the the centre uses the guidelines as a reference for its monitoring of displacement in roughly 50 countries. “The major achievement is that we have a common set of principles, which are the basis for all actors interacting with displaced persons, and for the displaced persons themselves, who now have a clear articulation of their rights.”

Acceptance of the Guiding Principles by international forums has enhanced their status as a universal point of reference. The most important development, however, may be the integration of aspects of the Principles into national law.

“We’ve used the Principles at key points to make significant inroads to influence national legislation,” said Ramesh Rajasingham, who heads the Displacement and Protection Support Section of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Geneva.

Kälin points out that one of the strong messages to be delivered in Oslo is the need to incorporate the Principles into domestic law and policies, but he adds that this can be a tricky proposition when a law protecting IDPs is contradicted by others already on the statue books.

Oslo meeting

“We are pushing the idea that governments have to look carefully at their existing legislation,” he said.

To facilitate that, a handbook on the legal aspects of the Guiding Principles has been prepared for the Oslo meeting.

Another helpful document is an annotated version of the Guiding Principles prepared by Kälin’s office. This provides the links between the principles and international law.

“At the end of the day, you need to make the link between ‘soft law’ and ‘hard law’, said Anne Zeidan, who heads the IDP project for the International Committee for the Red Cross. “You can’t just go with the Guiding Principles. It is important to remember that behind them there is a whole body of human rights and humanitarian law.”

Another major topic for discussion in Oslo is the growing population displacement resulting from natural disasters and climate change. “We expect that the number of people displaced by natural disasters will increase exponentially as climate change begins to take hold on disasters,” said OCHA’s Rajasingham.

The major emphasis, Kälin said, will be on consensus building, and climate change. “What I also hope to see emerge,” says Kälin, “is a kind of consensus on the displacement effect caused by natural disasters.”

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also