GAMBIA: President’s herbal HIV/AIDS 'cure' boosts ARV use

President Yahya Jammeh’s traditional herbal treatment for HIV has had an unanticipated side-effect, say HIV experts in the country – rather than pulling people towards a herbal cure, it has raised the profile of conventional antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) to treat HIV.

Twenty months since President Jammeh claimed to have discovered a cure for AIDS, antiretroviral treatment is on the increase while fewer people are stepping forward to participate in the President’s programme, according to an HIV/AIDS expert in the Gambia who asked not to be named.

People who were originally on antiretrovirals then switched to the President’s herbal treatment have since returned to ARVs.

“The [President's] treatment has improved the uptake of antiretrovirals by reducing the social stigma of HIV-positive status and by making people realise traditional treatments do not always work,” the source said.

While there is increasing scrutiny of the President’s treatment and its impact among HIV/AIDS experts and people with HIV/AIDS in The Gambia, the subject remains highly sensitive and none of those contacted by IRIN wished to be named.

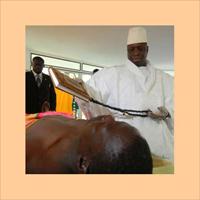

President Jammeh claimed in January 2007 to have discovered a herbal cure for HIV/AIDS, and launched a programme to treat people living with HIV/AIDS (PWLHA) for several months after which they are discharged from his programme. The claim triggered widespread condemnation from the international community, with health experts concerned it would slow the already low uptake of antiretrovirals, the only medically proven therapy for HIV infection.

The ingredients of the President’s herbal mixture have been kept secret.

Kevin Peterson, head of the British institute Medical Research Council’s (MRC) HIV treatment programme in The Gambia, estimates that on average 2 to 3 percent of Gambians are HIV-positive, and “the overall pattern is a gradual increase.”

Shift in language

President Jammeh recently started to modify the language he uses to describe his herbal treatment, according to the HIV/AIDS expert. “He no longer says people have been ‘cured’ through it, but instead that ‘no virus has been found in their system [when they graduate].’”

But this is not the case for all 'graduates'. One HIV-positive person was enrolled in an ARV programme but left it to pursue the President’s treatment. “The [President’s] treatment didn’t work out for me. I was sick all the time, my viral count shot up to 800,000 and I developed tuberculosis."

Upon completing the President's treatment, the patient returned to antiretrovirals and underwent several months of treatment in hospital before being diagnosed with an undetectable viral load.

Many people living with HIV/AIDS were afraid to speak on the record. “[If I speak], the President might arrest me…and my family will suffer from it,” one said.

Support for ARVs

But while continuing to provide his alternative herbal treatment, President Jammeh is also now a strong supporter of the National AIDS Secretariat [NAS], which coordinates clinics, non-profits and other organisations to provide conventional ARV treatment across the country.

NAS director Alieu Jammeh sees the President’s treatment as “complementary” to conventional ARV care, but said: “NAS, which sits under the President’s office, funds only conventional ARV treatments.”

The Gambia has received US$34.4 million from the Global Fund against AIDS, Malaria and Tuberculosis since 2004, and people living with HIV/AIDS are eligible for free treatment for HIV and all opportunistic infections.

Reducing stigma

One effect of the President's treatment programme is that by treating PWLHA himself, he has helped dismantle the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS, said Lamine Moko Ceesay, who also participated in the President’s programme. “He invites patients in, spends hours with them each day, and massages them with herbs. All this has helped people become more accepting of people living with HIV/AIDS in their homes and communities.”

The President takes about a dozen patients at a time, and treats them over a series of months, according to Ceesay, one of the first Gambians to publicly disclose his HIV-positive status.

“When I disclosed [in 2000] there was mass silence on HIV, but since then, attitudes have changed. There has been no pointing of fingers at me, people have only encouraged me,” he said.

He now works with non-profit Catholic Relief Services, going village to village to discuss how communities can care for people living with the virus.

“Recently when I have been talking to PWLHA in these villages,” Ceesay said, “not one of them spoke of rejection by their communities.”

But NAS director Jammeh says more needs to be done to stop discrimination, particularly among at-risk groups.

He said this should go hand-in-hand with a national strategy on HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment that would achieve basic steps such as ensuring the safety of blood stocks once people are tested, and monitoring prevalence rates. NAS is currently drawing up a five-year Global Fund proposal to fund this work. “We cannot be complacent. We want to make sure we halt prevalence rates, and reverse it.”

And this, he said, requires the full support of the President.

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also