LESOTHO: A village tries new ideas to beat climate change

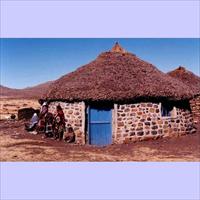

Chief Paulosi Lebakeng is a troubled man. Food production has dipped in his village of Ha Tsiu, perched about 2,500m above sea level on the Thaba Putsoa mountains, about 100km east of Lesotho's capital, Maseru.

Rainfall has become less frequent every year, as has snowfall; both important sources of water for food crops. There are more HIV/AIDS orphans in the village, and the pandemic has also left fewer people to work in the fields. Then, last year, the price of maize, the staple cereal, began to climb.

"People don't have enough to eat," he says in Sesotho. "It was never like this in my grandfather's time." The wind howls around his one-room mud-and-stone house as if in agreement. The name of the village in Sesotho means "This village belongs to many years" (it has existed for a long time).

Time is a critical factor in the villagers' lives. Ma Theko Mokhachane, a village elder shelling beans nearby, interjects, "We didn't have enough snow this year. The soil is not moist enough for planting maize. In our grandfathers' time we used to start planting by August; now it's getting later and later." When planting is late, the young maize sprouts are exposed to frost in April the following year, which kills most of them.

The fields have been tilled and now await the rains, but the forecast for the rest of 2008 and early 2009 is quite gloomy, according to Peter Muhangi, a project officer with the Lesotho Vulnerability Assessment Committee (LVAC), based in Maseru.

The people of Ha Tsiu realise that something is very wrong with the weather. Lebakeng asks the IRIN reporter: "Do you know what is happening?" He, Ma Mokhachane and his wife, called Ma Lebakeng by the villagers, are amazed to learn of the connection between their lives and the greenhouse gas emissions of industries and cars in cities far away.

They look up at the sky, trying to spot the gases warming up their part of the world. "Yes, the sun has been getting hotter," says Ma Mokhachane.

Scenarios based on projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change show that by 2045 Lesotho will face severe water shortages, and the government's national report on climate change has noted that there will be even less rainfall by 2075.

In 2007 Lesotho was ravaged by one of the worst droughts in 30 years, which left 400,000 people - a fifth of the country's population - in need of food aid.

The villagers are still trying to get back on their feet. The more than 1,000 residents, mainly farmers and herders, were forced to sell their animals – donkeys, horses, sheep, goats and hens - as a coping mechanism. In neighbouring villages some animals died. "In the old days, each family had at least 10 animals, now they are lucky if they have one," says the chief.

The village overlooks the Mohale Dam, one of two built as part of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), the world's largest water transfer operation; the other is Katse.

The dams were built in the Thaba Putsoa mountain range in southern Lesotho on the Senqunyane River, which becomes the Orange River when it reaches South Africa, at a cost of US$4 billion, to supply water to neighbouring South Africa's rapidly expanding industrial hub in Gauteng Province.

In terms of the water-sharing agreement between Lesotho and South Africa, the villagers, whose parched fields lie around the dam, can only access water to drink. They eye the dam with some resentment.

Lesotho's natural renewable water resources are estimated at 5.23 cubic km per year (km3/yr), far exceeding its water requirements, according to the Encyclopaedia of the Earth, but because of Lesotho's commitments in the framework of the LHWP, its actual water resources will have decreased to 3.03 km3/yr by 2020.

Alternative income at a cost

Over the years, more and more villagers have been forced to seek jobs across the border in neighbouring South Africa, the region's economic hub. Economic migration, temporary in most cases, exposed the village to HIV/AIDS.

Lesotho's HIV/AIDS prevalence rate of 23.2 percent in a population of 1.8 million is one of the world's highest, and the country has more than 100,000 HIV/AIDS orphans.

Ha Tsiu has 74 HIV/AIDS orphans. "There are at least five child-headed households in the village," says Lefulesele Sutha, principal of the local primary school.

Adapting to survive

Chief Lebakeng has begun to mull over possible solutions. "I am thinking of a communal grain reserve so no one will starve in the village," he says. The people already share their produce and the idea would be welcomed.

They are learning to use the wetlands near the fields as a source of water for irrigation, "But it is still underutilised," says Moliehi Shale, a researcher with the Climate Systems Analysis Group at the University of Cape Town.

Shale is part of a research team working on an European Union project, New Approaches to Adaptive Water Management under Uncertainty (NeWater), which has 43 scientific partners and has case studies from the river basins of the Rhine, Nile, Elbe, Tisza, Guadiana, Amudarya and Orange.

The objective of the project was to support the transition to more adaptive water management, particularly in the face of the uncertainties associated with climate change and other global shocks.

Lesotho lies entirely in the Orange River Basin, and the study examined the use of the wetlands by the residents of Ha Tsui as a source of water and food for their livestock.

In the past few years, some have begun to plant apple trees and grow garlic as alternative sources of income, "But not everyone can afford these trees, and you need many trees to make money," says Lebakeng.

"You can maybe earn R50 [a little more than US$6] a tree," says Ma Mokhachane. The money can buy around 10kg of maize-meal, which could feed a family of four for a few days.

The people are also considering other ideas. "Some of the villagers can learn to make handicrafts with grass," says Lebakeng, but Makoanyane Letsora, a subsistence farmer, points out that "We need someone to market our produce; I cannot even find a place to sell my apples."

Researcher Shale is exploring the villagers' understanding of climate change and the need to find alternatives to subsistence farming. "It is evident so far that the villagers would not like to leave their land and would prefer to find solutions here," she said. "The farmers in the village already shop around for drought-resistant seeds." Some are now part of a potato cooperative.

But Ha Tsiu is one of several hundred villages tucked away in the Lesotho highlands; about 80 percent of the country's population live in rural areas and struggle with the eccentricities of the ever-changing climate.

Some help on the way

Food production in Lesotho has been hit by various factors, including climate change, says Memed Gunawan, country representative of the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). "Thirty years ago, the country produced enough to meet its national requirement – it was an exporter of cereals and vegetables - now it barely manages to produce 30 percent of the requirements."

Besides the frequency of natural disasters, such as droughts as a result of climate change, lack of investment, economic migration and HIV/AIDS have all affected agriculture. The government spends a little more than two percent of its gross domestic product on agriculture, far below the 10 percent stipulated for African countries to achieve food self-sufficiency.

The FAO is looking at ways to help the country overcome the challenges of climate change. "We are also trying to develop some irrigation strategies," says Gunawan. "We are looking at training people in conservation farming techniques, which does not require a lot of water."

Conservation farming minimises soil disturbance, applies more precise timing for planting and utilises crop residue to retain moisture and enrich the soil.

The government has identified several ways of adapting to climate change, such as developing high-yield crop varieties, conserving rangelands to prevent soil erosion, and afforestation.

However, it says its adaptation plans are challenged by the communal land tenure system, which provides little incentive to the individual to improve or protect arable land and communally grazed resources; by poverty, which curtails the ability of many households to engage in conservation activities that may require purchased inputs; and by the low priority accorded to conservation by the Basotho.

See Also

- Greenpeace opens African Office -- focusing on climate change, deforestation and overfishing

- Greenpeace opens African Office -- focusing on climate change, deforestation and overfishing

- AFRICA: One voice on climate change

- Greenpeace opens African Office - focusing on climate change, deforestation and overfishing

- Indigenous peoples threatened by climate change

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also