MALI: Cooking with poison

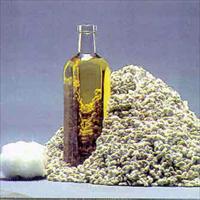

Cut-price cooking oil used in most Malian households has been found to contain gossypol, a toxic substance that is known to cause sterility, cancer and inhibit growth.

Only two out of 57 oil producers studied around the country had the necessary equipment to produce safely-refined cooking oil, revealed a November 2007 investigation by the Mali government. The rest were producing oil containing gossypol, a harmful poison.

“The results are alarming…after evaluating the oil mills, we realised most of them did not have proper refining equipment,” Adama Konaté, the government industries director told IRIN.

Gossypol is naturally produced by cotton plants to slow down the reproduction of insects that eat cotton seeds, and is eliminated if the oil refining process is conducted properly.

The majority of Malians buy the oil for cooking since, at an average of US$1.25 a litre, it is about half the price of imported oils.

Government order

Responding to the possible threat to consumers, on 15 January the government ordered 104 factories across the country to close down – a move some consumer groups say will not work unless it is accompanied by systems to monitor oil quality.

Most cottonseed in Mali is produced by small companies, but a handful of large ones have the right equipment and are capitalising on the closures to increase their market share.

Gossypol is linked with a host of health problems, including permanent infertility or sterility in men, irregularity of menstruation and termination of pregnancies in women, and gastric problems, according to Sanagaré Ibrahim, a nutritionist and a member of the Mali consumers association (ASCOMA).

Adama Haidara doctor at the Hope Clinic, a medical centre in Sikoro near Bamako, backed this up, stressing it is also linked to cardiac arrests and cancer.

“The risks to the consumer after a long period of absorption of non-refined oil are enormous.”

Updating too costly

The government has ordered producers to update their equipment, but not all can afford to and some have been forced to shut down production for good.

“Personally, I can’t afford to install a refinery system, so I closed my factory, and will sell it,” Seydou Traoré, an oil-producer in Fana, 120 km east of Bamako, told IRIN.

For Adama Tangara, who works with one of these firms, the answer is clear-cut, “Small oil producers can either buy new equipment or get out of the market.”

Meanwhile, Malians are taking their anger out on the government, accusing it of not regulating the industry properly.

"The government had no controls in place, no follow-up, nothing…the quality of the oil produced, and the health of consumers mattered little to it,” said Seydou Samaké, a Bamako resident who used to frequently cook with the oil.

“The doctor has arrived after the death. It’s always like that. It took us being poisoned for the government to intervene,” complained Oumar Traoré, a member of the Mali Coalition for the Protection of Consumers (REDECOMA).

Industries minister Konaté defended the government’s decision. “All the producers who had been approved were far from meeting the requirement to produce quality products… hence our decision to immediately close all the plants that did not meet these standards.”

Consumer policy needed

Members of the consumer’s group ASCOMA, which claims it was the first organisation to draw the dangers of gossypol in cooking oil to the government’s attention, agreed that the government has work to do if Malians are not to be hit by a similar crisis.

“We salute the government’s decision to close the factories, but that is not enough. It needs to put monitoring in place to control the quality of…all the products on the market,” Colibably Salimata Diarra, President of ASCOMA told IRIN.

She urged the government to create a labelling system so consumers can source the oil they have bought, to launch a campaign to alert the public to potential health risks, and to develop a national consumer policy to bring more accountability into the cooking-oil market.

All eyes are now on the government’s next steps. If there is no progress, some are urging strong action. "If the state does not do this, consumers must form a common block, and sue the State in front of a tribunal,” said Traoré.

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also