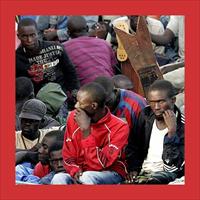

NIGERIA: Government unprepared for returnee influx

The Nigerian government has announced it is unprepared for the tens of thousands of returnees who have fled the southern Bakassi province over the past month, and is calling on the UN to help it handle the unexpected return.

Up to 76,000 returnees have registered at 12 sites in Akwa Ibom and Cross River states, according to Victor Antai, council chairman of Mbo, one of the sites in Akwa Ibom.

“We never envisaged such a flow of returnees,” Florence Ita-Giwa, head of the presidential task force on the resettlement and rehabilitation of Nigerian returnees, told IRIN. “It is because the situation in Bakassi [now under Cameroonian control] after the [14 August] handover has not been conducive, so they had to flee back to Nigeria. We had thought many of them would have stayed for at least a few more years.”

“There is an urgent need for the United Nations to come in and assist because people are stranded. People are all over the place,” she continued.

A five-year joint administration agreement was set up between Nigeria and Cameroon to ensure a peaceful handover and encourage Nigerians to remain in Bakassi, according to Ita-Giwa.

Youcef Ait Chellouche, disaster management coordinator for the Dakar office of the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC), told IRIN reports from the region indicate Bakassi residents feared persecution by Cameroon security services.

Nigerians started fleeing Bakassi following the 14 August 2008 ceremony between the governments of Cameroon and Nigeria, which officially handed over administration of the disputed Bakassi peninsula to Cameroon.

Returnees desperate

“Our infrastructure has been overstretched…Our resources can no longer sustain us. It has taken its toll on the council,” said Mbo councilman Antai. The normal population of more than 100,000 in Mbo, the closest point to Bakassi on the Nigeria mainland, has swelled to 180,000 according to him.

In the Akwa Ibom state capital of Uyo, about 1,000 displaced returnees stormed the governor’s office on 22 September to protest what they called ‘inhumane’ living conditions and the lack of federal aid, spelling out their complaints on hastily-cobbled signs: “We are Bakassi returnees, Please Help Us, “Please Help Us, We are Dying, and “We need Shelter, Please Help,” according to observers.

Ikpe Okon Awonshak, one of the protestors, said he felt he had run out of options. “Perhaps we should have stayed back in Bakassi to be killed by the Cameroonian soldiers, rather than come back and face these harsh conditions. We are dying here, our children are malnourished and the medical facilities are inadequate.”

There is as yet a skeletal humanitarian presence on the ground and has been no thorough independent assessment to analyse the situation on the ground in Bakassi, why people have been leaving the peninsula in such large numbers, or what their next steps will be.

Reports of deaths

Local Nigerian media reported on 22 September the deaths of 15 returnees, of which there has been no independent confirmation.

Mbo councilman Atai confirmed separate casualties at an Mbo camp where two people died of high blood pressure.

Government efforts

Essien Ayi, a Bakassi representative in the federal government, told IRIN Bakassi returnees are entitled to federal housing and resettlement help.

“It is the duty of the states, in conjunction with the federal government, to find a way to resettle all returnees because when the handover took place, the government said Nigerians had two options; to come back and be resettled, or remain as Nigerians in Cameroon. So those who opted out should be resettled…as soon as possible.” Ayi said.

The national government provided US$17 million to Cross River state to build a permanent settlement for the returnees; so far, 140 new houses have been completed, but work on the estimated US$200 million settlement has slowed because of money problems, according to resettlement task force member Ita-Giwa.

With federal attention focused on Cross River, authorities in neighbouring Akwa-Ibom cry negligence. “80 percent of the displaced people from Bakassi were originally from Akwa-Ibom,” Antai insisted, “My plea is that the federal government should come to our aid as well…We need to improve the general hospital and build more primary and secondary schools because enrolment is about to jump by 100 percent.”

International efforts

Ita-Giwa says it us the UN’s responsibility to help, given it helped broker the Green Tree Bakassi handover agreement after the International Court of Justice Ruling in 2002.

According to Olivia Hantz at the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the UN Office for West Africa is dispatching a human rights team to assess the situation, while other UN agencies are monitoring developments. “It is not yet a humanitarian crisis,” said Hantz, “but we will watch closely to see if that changes.”

The IFRC is sending an assessment mission within the next week to determine how many people need support, what kind of support they need, and how to help the government meet these needs in the short term while stressing that the IFRC's efforts will be finite.

According to the IFRC's Ait Chellouche, a 2006 government census listed only 32,000 people in the Bakassi peninsula, so the numbers need to be verified. It is possible, he says, that some who have moved, do not originally come from Bakassi.

“The situation is chaotic”, said the IFRC’s Ait Chellouche, “we need to establish the facts. The situation can change very quickly."

As national and international groups start answering their calls for help, returnees remain despondent. Returnee Affiong Okon told IRIN, “We really don’t know what plans the government has for us. We are in the dark concerning our future.”

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also