SENEGAL: Why the`talibe’ problem won’t go away

Empty cans used for begging line the entrance of a house in the overcrowded neighbourhood of Grand Yoff in the Senegalese capital, Dakar, where a `marabout’ [Koranic teacher] and 10 boys rent two mosquito-infested rooms.

The boys sleep together on the concrete floor. Each morning they get up, take the empty cans and head onto the street to beg for breakfast.

These boys are `talibes’, followers of a `marabout’, to whom they were entrusted by their families to learn the Koran. But their `marabout’ - like many others who are caretakers of an estimated 10,000 children in Dakar and up to 100,000 across the country according to UNICEF - does not have the means to support them.

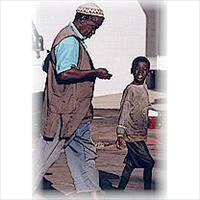

Thousands of `talibes’ spend hours each day walking the city in search of scraps of food and begging for money to meet a daily quota exacted by their `marabouts’, or face beatings, talibe children told IRIN.

Often with ripped clothes, barefoot and filthy, the children move alone or in packs. Many never learn the Koran, officials from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) say, and rarely do they attain adequate schooling that will lead to jobs when they become adults.

Despite the efforts of NGOs and government agencies to tackle the problem, it continues and may, according to some aid organisations such as Samusocial Sénégal, it may be growing.

NGOs Worldvision and Tostan and government officials from the Ministry of Solidarity cited three main obstacles to solving the problem: persistent poverty, an inadequate response by the government and the power of `marabouts’ in Senegalese society.

“The [`marabout’] system goes above the president,” said Ann Birch, communications leader for World Vision Senegal, and a photographer who has documented `talibe’ children.

People consult `marabouts’ on family matters, money questions, for professional advice, and even guidance on how to vote, Imam Mamadou Ndiaye, director of teaching at the Islamic Institute of Dakar, told IRIN. They are influential in all levels of society.

Financial stakes

`Marabouts’ demand that their `talibes’ give them a daily average minimum of 350 CFA francs (77 US cents), according to various children IRIN interviewed. That is a considerable sum in a country where over half the population lives on less than two dollars a day.

“The economic stakes are enormous,” explained Isabelle de Guillebon, director of Samusocial Sénégal, one of many local NGOs working with street children in Senegal.

“People are making more money off [child] begging than they would if they had jobs,” said Mouhamed Chérif Diop, programme coordinator for the local NGO, Tostan, which helps to reintegrate `talibes’ with their families.

A hesitant government

In 2005 the government passed stricter laws against begging, including stronger sentences for mistreating children. But what is missing, many NGO representatives told IRIN, is government-wide regulation of the Koranic schools.

According to Tostan’s Mouhamed Chérif Diop, “until the government regulates the thousands of informal Koranic schools so that not just anyone can open a `daara’ [Koranic school] the problem will not go away.”

The government is currently creating ‘modern daaras’ in which children do not go out to beg. But “there is lots of talk and very little action,” says Isabelle de Guillebon, director of NGO Samusocial Sénégal. “These steps are more for show and the anti-begging law isn’t being enforced.”

Some officials in the government even blame the persistence of `talibes’ on elected politicians, whom they say are unwilling to tackle the issue. “The state does not want to commit itself to solving the problem because it touches on religion,” Amadou Camara, head of non-conventional learning at the Ministry of Solidarity, told IRIN.

“In every big city, there is a religious leader who has disciples in high places in the social administration.”

Some officials said the solution is to help `marabouts’ generate revenue so they do not need their pupils to go out and beg.

Piecemeal approaches

The government Ministry of Solidarity has funds to support up to 100 `daaras’ every year to try to reduce `marabout’ dependence on begging for income, said Camara, adding that some schools could come away with 500,000 CFA francs a year (US$1,105).

Some NGO officials do not see that as a solution. “It endorses an abnormal situation,” said Mouhamed Chérif Diop, programme coordinator for Tostan. But Camara said: “If you give absolutely nothing, it’s even worse.”

NGO officials admit that their programmes are too small and uncoordinated to address the problem. “We do [all we can] with our limited means,” Samusocial Sénégal’s de Guillebon said, “but little actions we do of returning three or four children [to their families] is not going to solve the problem for 10,000 child beggars in Dakar.”

Some NGOs have tried to encourage `marabouts’ in Dakar to return home to their rural villages and find alternative incomes. With support from the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the NGO Enda has helped one `marabout’ and 47 `talibes’ return to his [the `marabout’s’] home village of Pout, where he now grows vegetables and no longer sends his pupils begging.

But “actions are not systematic or on a big scale,” ENDA’s resource coordinator, Moustapha Diop told IRIN. “There needs to be a much more global approach.”

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also