SOUTH AFRICA: Country needs free universal education

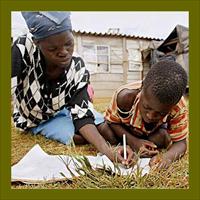

The South African government should aim for free universal education, backed up by teacher training so as to make a significant impact on the quality of schooling, said the country's largest public service union.

Jon Lewis, spokesman for the South African Democratic Teachers' Union (SADTU) said the plan by the ruling African National Congress (ANC) to extend free education to 60 percent of schools in 2009 should be applauded, but it was not without glitches.

"The process of identifying and assessing poor schools which would benefit from the plan is quite problematic," Lewis said. Schools were often found to be either poorer or richer than the assessment process had classified them, and he recommended that the country "rather go for free universal education."

The ANC announced the decision to extend the "No Fee" school model from the poorest 40 percent to 60 percent of schools at its conference in Polokwane, Limpopo Province, in December 2007.

Lewis said the government should also concentrate its efforts on trying to improve the quality of education by capping the maximum number of students in a class at 30, because "We have anecdotal evidence that classrooms in rural schools often have 60 students."

According to government's most recent statistics, in 2006 there were more than 380,000 educators for more than 12 million learners, giving an average of around 32 learners per class.

One of the biggest stumbling blocks to improving school education has been the introduction of two new curricula in 15 years. "Teachers had started to get familiar with the first curriculum, introduced 12 years ago, when yet another was introduced six years ago. At one stage schools were struggling with two curricula and things got very complicated," said Lewis.

Training teachers and familiarising educators with the new curriculum and assessment process should be intensified. "Many of our teachers were trained 10 to 20 years ago and are not familiar with the new curriculum," said Lewis. Few workshops to help teachers with these areas had been held, and "Often the quality of training provided has been poor."

Downside to free education

There was also a downside to plans to provide free education, which could impact on a school's ability to raise financial resources. In many cases the income to be provided by the state to compensate for the loss of school-fee revenue would be lower, said Salim Vally, a senior education researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

"While taking away fees might make it easier for children to access, whether they will receive a meaningful education is questionable," he commented.

Auxiliary support

Vally said auxiliary support in the form of free school books and uniforms should be part of extending free education. A significant number of South African children, many of whom have been orphaned by the HI-virus, received free school books, clothes and a daily meal because of the impoverished existence they endured at home.

"The call for free education has been made by civil society for years, and the ANC's decision to provide free education must be applauded. But this step must be supported, as fees are just a fraction of the cost of going to school," said Vally.

"The cost of transport, school feeding programmes and administering education at local and provincial level is significant. While the money is there to pay for these programmes, the capacity to deliver, thus far, has been lacking and there are no signs that this has changed dramatically in recent months."

Poorly serviced schools

Schools also struggle with poor service delivery and equipment. Nearly 15 years after the advent of democracy in South Africa, thousands of schools across the country still have no sanitation, water, electricity, science laboratories or sports facilities, despite the education department having an annual budget allocation larger than any other government department.

Education Minister Naledi Pandor recently told parliament that just over 26,000 government schools in South Africa lacked at least one of a number of basic infrastructural needs, such as running water and electricity.

Pandor, whose statistics were compiled from research conducted in 2007 by the National Education Infrastructure Management System, revealed that 1,097 schools had no sanitation facilities, 2,568 had no piped water and 7,418 were without science laboratories. A majority of the schools worst hit by poor service delivery were in the Eastern Cape Province, an ANC heartland.

The education minister maintained that a significant number of schools lacking in basic services were earmarked for infrastructural upgrades during the 2009 school year. She said the department of water affairs and forestry planned to supply sanitation to 935 of these schools and 900 would receive running water.

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also