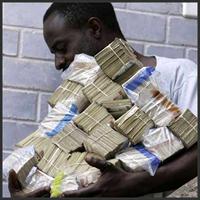

ZIMBABWE: How do you rein in 231 million percent inflation?

Zimbabwe's official annual inflation rate reached 231 million percent in early October, from the July estimate of 11.2 million percent, and the deadlock in talks between the ruling ZANU-PF and opposition parties is likely to push hyperinflation higher.

The state-run daily newspaper, The Herald, said the driver behind the inflation rate was wheat shortages that forced bakers to import ingredients, which led to a higher bread price.

After a succession of dismal harvests, attributed to environmental factors and political disruptions, nearly half of Zimbabwe's citizens will require food assistance in the first quarter of 2009, according to the UN.

Several attempts by President Robert Mugabe's government to bring down inflation - including lopping off ten zeroes from the currency, introducing a new currency, and price controls - have failed to put brakes on the multimillion percent inflation rate.

The importance of a political solution to counter hyperinflation was illustrated in the wake of elections this year, when the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) won a majority in parliament for the first time since independence in 1980, and MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai narrowly missed winning the presidency.

"There is a widely held perception that the Zimbabwe dollar is seriously undervalued in the parallel market. The sharp 65 percent appreciation of the Zimbabwe dollar on the parallel market in the immediate aftermath of the 29 March 2008 elections suggests that this is, in fact, the case," said a recent UN Development Programme (UNDP) discussion document.

Independent economists have estimated the real inflation rate at billions of percent: Zimbabwe's financial malaise is not seen as a direct consequence of Mugabe's 2000 fast-track land reform programme, in which more than 4,000 white-owned farms were redistributed to landless blacks, it is rather a series of injudicious decisions overlaying structural economic weaknesses inherited from the former Rhodesia that are being amplified.

Dual economy

At independence Mugabe's government inherited a dual economy "characterised by a relatively developed and diversified formal economy sitting alongside a neglected and underdeveloped peasant-based subsistence rural economy," according to the UNDP discussion document, Comprehensive Economic Recovery in Zimbabwe.

This dual economy has not been addressed by the ruling ZANU-PF during 28 years of power, and "with the collapse of the formal economy and the exponential growth of the informal economy both in urban and rural areas during the crisis period, the problem has deepened, with most economic transactions and units now operating outside formal systems," the discussion document commented.

The trigger for the current hyperinflation environment "can be traced to the so-called 'Black Friday' crash of the Zimbabwe dollar on 14 November 1997, which was precipitated by the government's unbudgeted payment of gratuities to veterans of the liberation war.

"This was followed in 1998 by Zimbabwe's participation in the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which further contributed to the ballooning fiscal deficit," the UNDP document noted.

Inflation rose from 19 percent in 1997 to 56 percent by 2000, when the land reform programme was launched - spearhead by the war veterans - so that by 2006 inflation was running at more than 1,000 percent and reached hyperinflation levels by 2007.

"Zimbabwe's inflation is fundamentally caused by excess government expenditure, financed by the printing of money in an economy with a real gross domestic product (GDP) that has been declining for the last nine years. Money supply growth has been completely decoupled from economic growth, the inevitable result being continued and accelerating inflation," the UNDP said.

Between 1998 and 2006 Zimbabwe's GDP contracted by 37 percent, and by 2000 per capita incomes were lower than those in 1960.

Accelerating poverty

Poverty has accelerated, according to the 2003 Poverty Assessment Study Survey (PASS II), from 55 percent of Zimbabweans living below the Total Consumption Poverty Line (TCPL) to 72 percent of the population by 2003, or an increase of about a third in eight years.

A rider to Zimbabwe's economic deterioration is the effect of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which UNAIDS and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) calculate may decrease GDP growth rates by between one and two percent.

About 1.6 million Zimbabweans between the ages of 15 and 49 years old are living with HIV/AIDS, although prevalence of the disease declined from 20.1 percent in 2005 to about 15.9 percent by 2007.

The document was written by Dale Doré, director of Shanduko, a Harare-based non-profit research institute on agrarian and environmental issues, Tony Hawkins, Professor of Economics at the Graduate School of Management at the University of Zimbabwe, Godfrey Kanyenze, director of the Labour and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe, Daniel Makina, professor of Finance and Banking at the University of South Africa in Pretoria and Daniel Ndlela, director of Zimconsult, a Harare economic consultancy firm.

The authors agree that the medicine to reverse the ravages of the economic mismanagement is likely to be as painful as hyperinflation's symptoms, and that the precursor of a pro-poor recovery would be "sound macroeconomic management".

"Full recovery, defined simply in terms of a return to the peak real per capita incomes of 1991, would take 12 years, assuming a bottoming-out of the decline in the course of 2008, and uninterrupted growth of five percent annually from 2009 to 2020," the discussion document noted.

"And, given that Zimbabwe is susceptible to drought - on average every three years - and that with the decline of commercial agriculture this vulnerability has increased, even the five percent annual growth in per capita GDP may be beyond the upper bounds of probability."

There is no one-size-fits-all remedy for hyperinflation, but there is consensus that delinking the political manipulation of the exchange rate and monetary systems is a prerequisite.

Drastic measures

Professor Steve Hanke of Johns Hopkins University in the US believes measures used internationally to restore economic confidence and rein in hyperinflation require "punishingly high" interest rates, causing slow GDP growth, stagnation of living standards and the worsening of poverty during the "stabilisation period."

Hanke contends in the UNDP discussion document that, should there be a political settlement in Zimbabwe, the new government has three options to consider: dollarisation, free banking, or a currency board, all of which have their pros and cons.

Dollarisation or randisation - the rand is the monetary unit of South Africa, Zimbabwe's neighbour and the continent's economic powerhouse - would entail one of the foreign currencies being made legal tender instead of the Zimbabwe dollar, which would die a natural death.

However, the new government would "no longer have an independent monetary policy and set their own interest rates, but must 'import' the monetary policy of the country whose currency is chosen," Hanke said in the discussion document.

A second consideration is "free banking", used in colonial Southern Rhodesia until 1940, in which private commercial banks issued currency notes with 'minimal regulation'.

The third consideration is a currency board, which would mean holding "foreign reserves equal to 100 percent of the domestic money supply determined at a fixed exchange rate ... as a result, money supply, and thereby interest rates, are determined 'entirely by market forces'."

Handing over "monetary policy to outsiders or even to market forces would be a high-risk strategy for a fresh administration," the UNDP discussion document said, especially in the light of Mugabe's consistent accusations that Zimbabwe's economic decline was a result of "former imperialists" trying to re-colonise the country.

"Furthermore, the suggestion that Zimbabwe should abolish its central bank when much smaller regional economies – Lesotho and Swaziland – find it necessary to operate a central-bank system, even though they are members of the Rand Monetary Area, is unrealistic," said the UNDP document.

Should there be some sort of political settlement, the creation of an independent central bank under a new constitution was likely to be part of the public debate.

"Given Zimbabwe's unhappy recent history with a politically driven central bank, the economic case for RBZ [Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe] independence is very powerful," the document noted.

Whatever solutions are used to tackle Zimbabwe's hyperinflation, its legacy will haunt the country for many years, and manifest itself in such areas as investor confidence - both local and international - and the rebuilding of "once strong" public institutions.

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also